Imagine your knee as a well-coordinated dance troupe, with each member playing a crucial role in maintaining harmony. Among these dancers, the Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) stands out as the powerhouse, ensuring your knee stays stable and strong. But what happens when this unsung hero gets injured? Let’s dive into the world of the PCL, exploring its anatomy, injury mechanisms, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation.

Anatomy and Function: The PCL Explained

The PCL is like the backbone of your knee, starting from the inner side of the thigh bone (femur) and attaching to the back of the shin bone (tibia). It’s twice as strong as its cousin, the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL), and its primary job is to prevent the tibia from sliding backward under the femur. Think of it as a bouncer at a club, keeping the partygoers (your bones) in line.

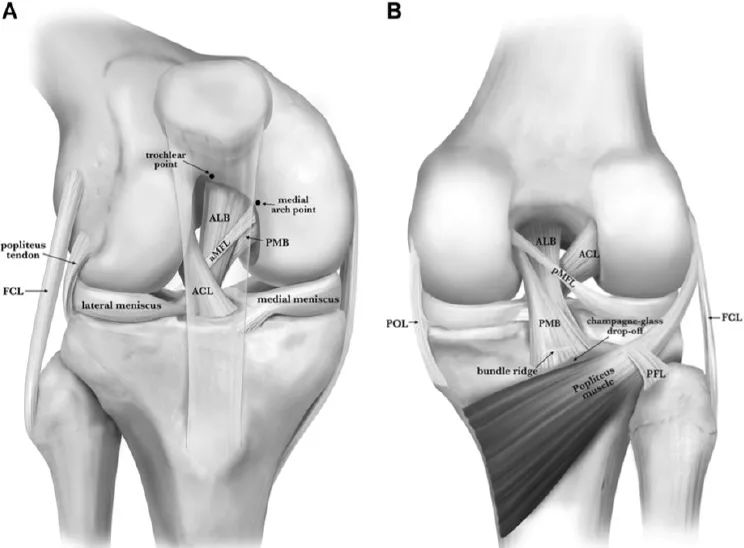

Figure 1: Anterior view (A) and posterior view (B) of the Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL). Emphasis is placed on the femoral and tibial attachment sites of the anterolateral bundle (ALB) and posteromedial bundle (PMB) and bony landmarks: the trochlear point, medial arcuate point, bundle ridge, and champagne glass drop. ACL, Anterior Cruciate Ligament; aMFL, anterior meniscofemoral ligament (Humphrey ligament); FCL, fibular collateral ligament; PFL, popliteofibular ligament; pMFL, posterior meniscofemoral ligament (Wrisberg ligament); POL, posterior oblique ligament.

The PCL is divided into two main bundles: the anterolateral bundle (ALB) and the posteromedial bundle (PMB). These bundles work in harmony, with ALB relaxing when your knee is straight and tightening when you bend it, while PMB stays tense during both straight and deep bending. It’s like having a team of bodyguards, each with a specific role to play.

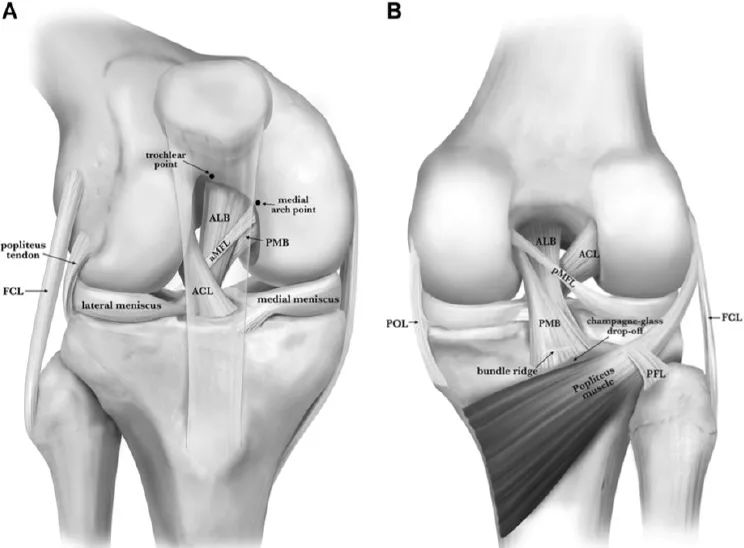

Figure 2: PCL injury. The American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine classifies ligament injuries into three degrees:

- Grade I: Minimal ligament fiber tearing, with local pain and no instability.

- Grade II: More extensive ligament fiber tearing, with some functional loss and joint reaction.

- Grade III: Complete ligament rupture, with significant joint instability.

How Does the PCL Get Hurt?

PCL injuries are often the result of a direct hit to the front of the knee while it’s bent, such as when a motorcyclist’s knee slams into the dashboard—a scenario known as “dashboard injury.” Ouch! Other causes include landing awkwardly from a jump, which can stretch or tear the ligament. Unlike other knee injuries, PCL tears rarely happen in isolation; they often come with other ligament injuries, making the situation even more complex.

Diagnosing a PCL Injury

If you suspect a PCL injury, your doctor will likely start with a physical exam. Common symptoms include pain, swelling, and difficulty moving the knee. Here are a few tests your doctor might perform:

- Posterior Drawer Test: This test checks if the tibia is sliding backward. It’s like trying to pull a drawer out from the back of a cabinet.

- Quadriceps Thigh Test: This involves feeling for any backward shift of the tibia when you contract your quadriceps muscle.

- Posterior Lachman Test: Similar to the Lachman test for ACL injuries, this checks for any backward movement of the tibia when the knee is bent at 30 degrees.

For more definitive answers, imaging tests like X-rays and MRI scans are often used. MRI is particularly useful, showing detailed images of the ligament and any associated damage.

Treatment Options

Unlike the ACL, the PCL has a natural healing ability, but this doesn’t mean it’s always smooth sailing. Treatment options vary depending on the severity of the injury:

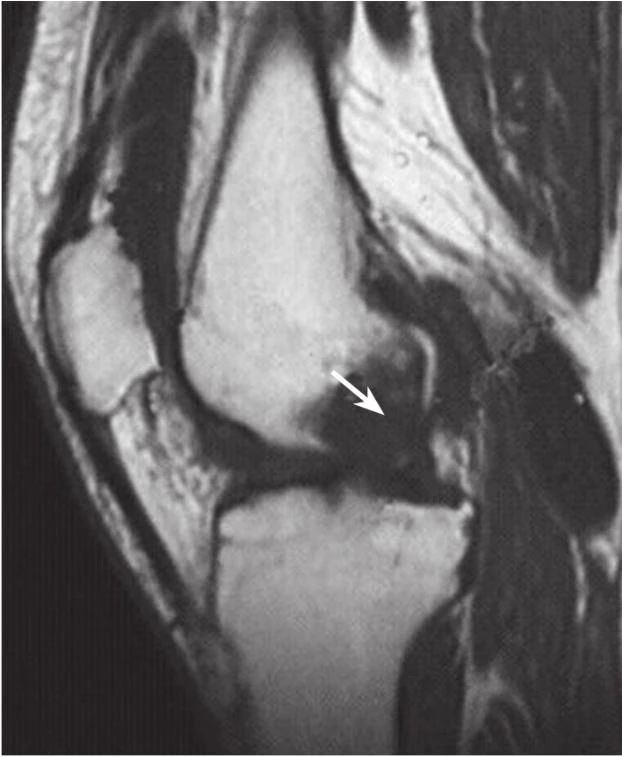

Figure 3: Schematic diagrams of posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction techniques via tibial and tibial inlay methods. Single-bundle (a) and double-bundle (b) tibial techniques (right knee, anterior view). Single-bundle (c) and double-bundle (d) tibial inlay techniques (right knee, posterior view).

- Conservative Treatment: For mild injuries, rest, ice, and physical therapy can help. This approach focuses on early movement and strengthening exercises to restore stability.

- Surgical Intervention: For more severe cases, surgery might be necessary. This could involve repairing the torn ligament or, in some cases, reconstructing it using grafts from your own body or donor tissue.

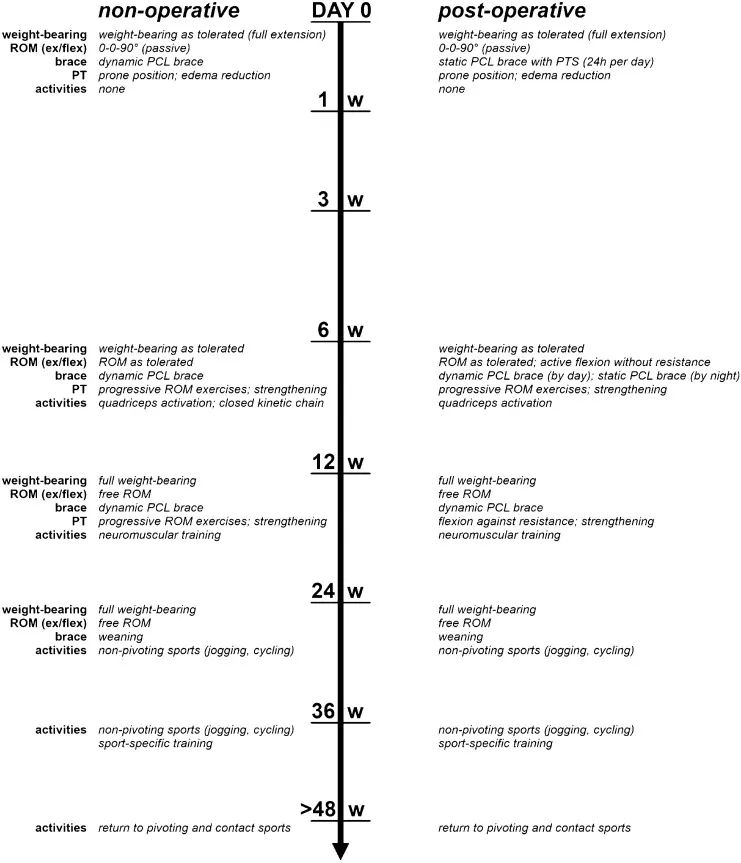

Recovery and Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation is crucial for both surgical and non-surgical treatments. It typically involves wearing a knee brace for support, gradually increasing activity levels, and focusing on strengthening the muscles around the knee. Physical therapy plays a key role, helping to restore range of motion and muscle strength.

Potential Complications

While PCL reconstruction surgery can be highly effective, it’s not without risks. Complications can include infection, blood clots, and even nerve damage. However, with careful planning and skilled execution, these risks can be minimized.

Conclusion

The PCL might not be as famous as its ACL sibling, but it’s just as important. Understanding its role, how it can be injured, and the treatment options available can help you make informed decisions about your knee health. So, next time you think about your knee, give a little nod to the mighty PCL—your knee’s unsung hero.

Leave a Reply